Our psyche, which is primarily responsible for all the historical changes wrought by the hand of man on the face of this planet, remains an insoluble puzzle and an incomprehensible wonder, an object of abiding complexity — a feature it shares with all Nature’s secrets. — Carl Jung

For Everyone

Neuromythography definition

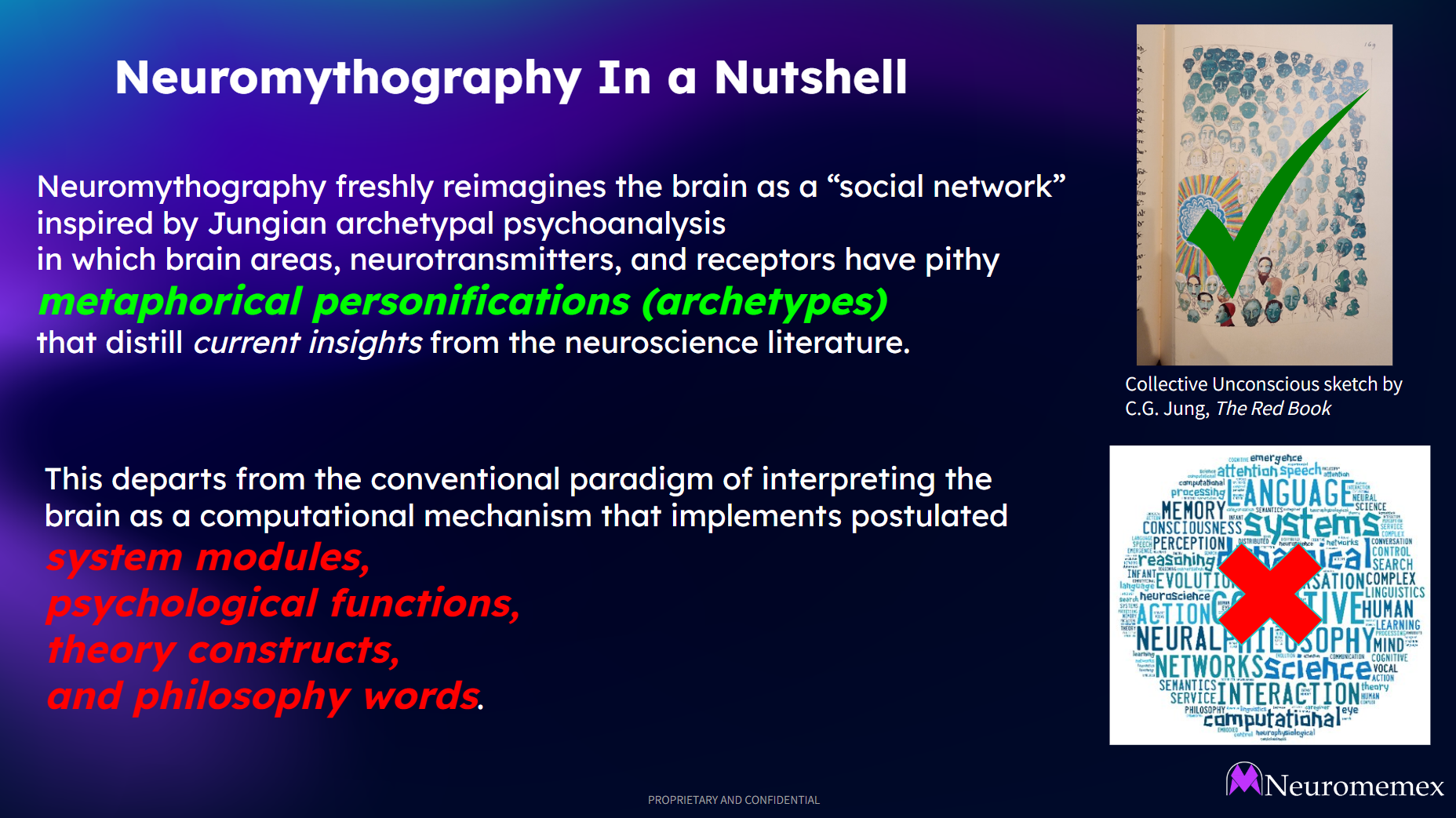

Neuromythography is the study of the neuroscience literature to create and refine a "mythological social network" graph model of the brain. This model is then annotated back to the neuroscience literature, and we can now understand each neuroscience study as a story in a bottom-up neuromythographic mythology. We call this graph database a 'neuromemex', an allusion to the original memex vision of Vannevar Bush in 1945.

The goal is to tame the complexity to create a more insightful model of the mind than is possible using obsolescent philosophy and social science paradigms. It also provides a reference meta-architecture for future artificial intelligence designs.

Neuromythography is a recursive portmanteau:

neuro-: pertaining to the brain

-mytho: pertaining to myths

-graph: a network data structure with nodes and links

-graphy: a process for recording and memorializing

-mythography: the cataloguing of myths and their artful expressions

Neuromythography is a new approach to understanding the brain that turns traditional neuroscience on its head, by reinterpreting it as a grand social network of more than 1,000 allegorical characters, connected by more than 24,000 connections. These have been built up by hand, after reading more than 100,000 neuroscience studies and innumerable fMRI images, curated into more than 8,000 annotated studies. Most reasonable researchers approach problems of this scale with machine learning and data mining; this left open the opportunity for an intensive artful approach enabled by, but not driven by, technology.

The most important principle of neuromythography is to avoid using abstract psychological nouns like 'attention', 'anxiety', 'inhibition', 'emotion', 'cognition', or 'aversion' in between the brain part and the allegorical character. It is our contention that it is these very psychological nouns--nouns that predate modern neuroscience knowledge--that get in the way of insight into the brain. Even modern psychology founder William James warned against "vicious abstractionism", a warning that his successors promptly ignored. Using loosely-coupled personifications ensures that the focus stays on the mysterious concrete anatomical or chemical entity, not the foggy abstraction that we hope the thing is a "mechanism" for. The archetype may be swapped out at any time for a better one as scientific insight into the physical entities proceeds, unlike mental theory constructs that tend to zombie on long past their useful expiration dates.

The standard terms used in neuroscience, like thalamus ("chamber"), locus coeruleus ("blue place"), and pineal gland ("pine cone") are Latin visual metaphors that were created thousands of years ago, when all early anatomists had to go on was the visual appearance of the brain area. Similarly, serotonin is a portmanteau of the Latin word serum ("watery fluid") and the Greek word tonikos ("an invigorating medicine"), which interprets early experimental observations that serotonin causes contraction of blood vessel smooth muscle. These terms work adequately for medical investigation, but over the past several decades we now have accumulated information about their psychological roles, for which these old names do not provide any insight. For this latter domain, a fresh set of interpretive alternate names can help. This is one of the aims of neuromythography.

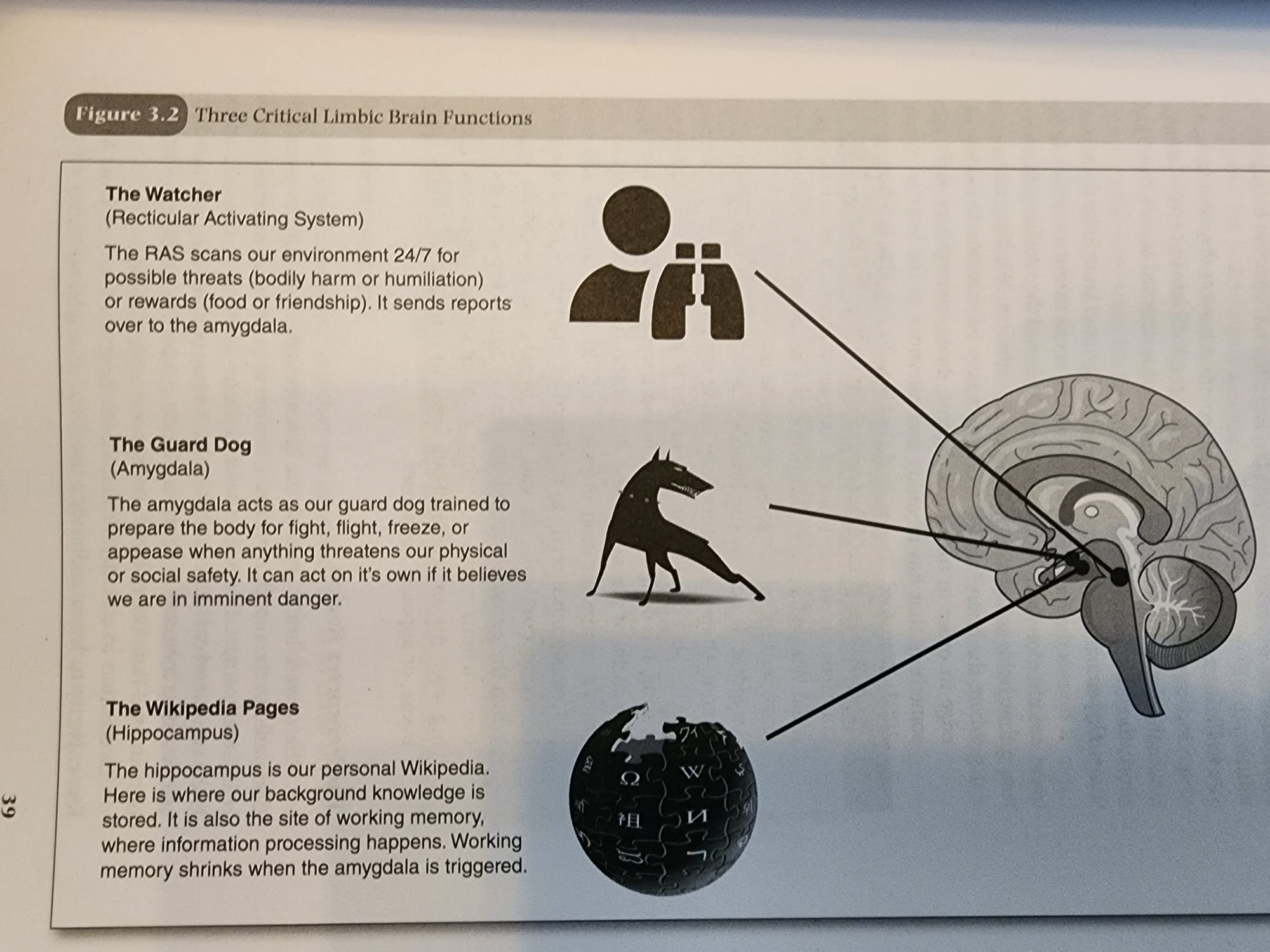

Instead of dry, complex terms and diagrams, neuromythography uses lively, engaging stories and characters, each representing different parts of the brain and how they interact. Imagine a world where dopamine isn't just a chemical, but a character, Samsara, navigating through cycles of interest and motivation, helping us understand why we feel compelled to keep going after goals, and reckon our proximity to them. Serotonin is Nirvana, an energy representing our confidence in our current model of reality and behaviors, amplified by the dorsal raphe nucleus, Aeternitas (Greek god of eternal staying power), with dissonant chords inserted by the median raphe nucleus, Moneta (the Roman goddess of warning memories). It's like turning the brain into a lively drama where each character plays a crucial role in the story of our thoughts, feelings, and actions. The characters Samsara and Nirvana correspond nicely with a couple of central concepts in Buddhism. Whether you think the Buddha was just using mystical language for things we were not yet ready to understand, or if the personification just provides a memorable metaphor for what science eventually revealed, the metaphor is a useful generalization that corrects the popular science myths of dopamine 'pleasure' and serotonin as 'happiness'. Crucially, we use these metaphors to integrate the insights of many researchers across scientific studies.

How do we do this? We processed, combined, and reconciled the insights of thousands of neuroscience researchers, and embedded them into a unique, artful, connected model of the brain.

Neuromythography does not provide simple answers. It offers a fresh way to frame the questions.

This method isn't just for scientists; it's for everyone curious about why we do what we do. By storytelling, neuromythography makes the intricate workings of the brain accessible to people of all ages and backgrounds. It's particularly great for young students or creative individuals who might find traditional scientific explanations intimidating or dull. Through neuromythography, learning about the brain becomes an adventure, where complex concepts become easy to grasp as part of a narrative.

Moreover, neuromythography encourages us to think about our own brains differently, fostering a deeper personal connection to the science of the mind. Understanding our brain's characters helps us better understand ourselves, leading to personal growth and insight. It makes us realize that our emotions and behaviors are influenced by an internal cast of characters who interact in complex ways, and by learning about them, we can perhaps direct the story of our own lives a bit better.

For Teachers

Neuromythography is a creative way to teach students about the brain that goes beyond typical science lessons. Instead of using complicated terms and diagrams, it uses stories and characters to represent different parts of the brain and how they work together. For example, Dopamine becomes a character who drives our desire to achieve goals and find new interests. This method makes the science behind our thoughts and feelings come alive, engaging students in a way that helps them easily grasp complex ideas about how the brain functions.

This storytelling approach can be a powerful tool to complement socio-emotional learning (SEL). While SEL focuses on developing skills like empathy, self-regulation, and teamwork, neuromythography articulates the brain science behind these skills. It helps students understand why they feel or react in certain ways, linking emotions and behaviors to specific characters in their brain's story. This can make lessons on self-awareness and relationship-building more relatable and impactful, providing a scientific foundation that complements the personal growth aspects of SEL, while avoiding critical pedagogy and other extraneous concepts.

For teachers, neuromythography offers a unique and imaginative way to enrich their teaching toolkit. It can spark curiosity and enthusiasm for learning about the brain and its influence on behavior, making the abstract concepts more tangible and memorable. By integrating neuromythography with SEL, teachers can provide a holistic education that not only fosters emotional and social skills but also deepens students' understanding of the biological processes that underpin these skills, promoting a fuller, more rounded approach to education.

The Neuromythography Institute is developing curricula suitable for different age groups. We welcome contributors. Please subscribe to our newsletter for updates.

For Creators

Neuromythography is an intriguing way for artists and creators to explore the human brain through the lens of art and storytelling. It uses characters and narratives to represent different parts of the brain and how they function. For example, think of Dopamine not just as a chemical but as a character in a story, who is always chasing goals and experiencing the thrill of new discoveries. This method brings the complex science of the brain to life in a way that is accessible and creatively stimulating, allowing artists to visualize and personify brain functions as characters in their scripts or visual art.

For scriptwriters, neuromythography offers a rich source of material for character development and plot creation. By understanding the roles different parts of the brain play in emotions and decision-making, writers can craft more nuanced and realistic characters. For instance, a character influenced by the 'character' of Serotonin in the brain might be depicted as calm and collected, handling stress well under pressure. This approach can deepen the audience's engagement with the characters, as they see a reflection of real human psychology in the actions and developments on screen.

Visual artists can also benefit from neuromythography by incorporating the symbolic representations of brain functions into their art. They could create visual metaphors that depict how different brain parts interact, like showing a dance between characters that represent Serotonin and Dopamine, illustrating the balance between calmness and excitement. This can add a layer of depth to artworks, making them not only beautiful but also intellectually stimulating and educational.

Moreover, neuromythography encourages a deeper connection between creators and their own creative processes. By understanding the neuroscience behind creativity and emotional expression, artists can better manage their creative blocks and find new sources of inspiration. Knowing which 'characters' in their brain might be responsible for certain feelings or creative bursts can help artists tap into those areas more effectively and purposefully.

In conclusion, neuromythography is a powerful tool for artists and creators, enriching their work with deeper psychological and scientific insights. It bridges the gap between the arts and sciences, offering a unique perspective that can inspire new creative techniques and expressions. Whether in scriptwriting, visual arts, or other creative fields, neuromythography provides a fascinating way to explore and depict the human condition through the dynamic interplay of our brain's many parts.

For Neuroscientists

Neuromythography is a fresh method and rich information model built atop a hyper-detailed interpretation of modern neuroscience, that attempts to bypass the obsolescent abstract psychological jargon that, we argue, hinders understanding. The coming of something like this has been long been foretold by the eliminative materialist prophets. Our expression medium of choice is myth, which is certainly not what the eliminative materialists had in mind, but represents a good comeback story for the Jungian psychoanalysts. Neuromythography is rigorous, painstaking, artful, and very serious fun, and designed to liberate neuroscience from the creaky Enlightenment-era pantheon of abstract mental nouns–"reities", if you will--that neuroscientists are constrained to.

The summer symposium of the Terran Society of Zeta Reticuli, the home planet of the famous grey aliens, had a focus topic:

What is the Function of Tommy Karevik?

Tommy Karevik is a fireman in Sweden. He is also the current lead singer of Kamelot, a US-based band based in Tampa, Florida, whose style is classified as European symphonic metal. Is he a fireman or a singer? Is his presence sufficient to classify Kamelot as a European band even though it is based in Tampa? The discrete function of this human was challenging for the alien researchers to determine definitively.

One faction, whose adherents were categorized as occupationalists, argued that function should reflect what an entity spends most of its time doing. They argued that the function of Mr. Karevik is to transport water to fires in order to restore local temperature homeostasis.

Another faction, known as the kleosists (after the ancient Greek word kleos, meaning 'fame'), argued that function should reflect what an entity is best known for. They deemed the function of Mr. Karevik to be primarily to produce harmonic vocalizations synchronized to pacing rhythms.

A third faction, the evolutionary psychologists, argued that the evolutionary function of Mr. Karevik is to provide European symphonic metal music behaviors to the band necessary to survive in an otherwise hostile American musical environment. These researchers were stand-up performers skilled at improvising an ad hoc origin story when handed a behavioral trait on an index card. Mr. Karevik was therefore simply an adaptive mechanism that sprang forth from the invisible hand of convergent evolution.

A fourth faction, the philosophers, admonished that the entire discussion was an example of the mereological fallacy. Fires are fought by fire departments, not individual firemen. Bands perform a band's music, not individuals. It makes no sense to ascribe functions to a particular component--Mr. Karevik--that philosophers have exclusively reserved to the whole organism.

A fifth faction argued that it made no sense to speak of the function of Tommy Karevik altogether except as a cog within a "system of interlocking, interdependent cultural logics". Everyone nodded politely, for they knew that this faction had a penchant for public denunciations of their enemies.

A sixth faction, who were known for theories of people that begin with the letter ‘E’, proposed to transcend Mr. Karevik himself by proposing that the fifth faction’s cultural logics were “emergent, embodied, enactive, and extended” from Society, with the totality representing a complex, dynamic, irreducible system, and that characterizing Mr. Karevik in particular was not even metaphysically possible.

A lone researcher spoke up from the back. She asked the audience, "What if Tommy Karevik just does what a Tommy Karevik does? What if we just got to know who he is by studying how he behaves in different situations, where he comes from, and who he interacts with, instead of trying to stuff him into our ill-fitting why theories? Has anyone read the Taoist Zhuangzi and his parable of Butcher Ding, and reflected upon the importance of 'cutting nature at its joints' instead of projecting our own pre-existing categories upon it?"

The audience stared at her blankly, with dark lidless eyes. Telepathically, the panel chair, a galaxy-renowned philosopher of science and ornithologist, called for a recess. He quietly ordered an implementation of the Hippasus Protocol, a cultural custom that the Zeta Reticulans had adopted from the Terrans.

After much lively discussion, the symposium panel ultimately agreed upon a consensus position: more study funding was urgently needed. In the concluding remarks, the chairperson announced the topic of next year's session:

"What is the function of the Terran brain nucleus known as the periaqueductal grey: fight, flight, freeze, fear, panic, hunting, music pleasure, species-specific vocalizations, joy, maternal behaviors, spirituality, sexual motor control, urination, or involvement in modulating flexible behaviors adaptive to dynamic environmental contexts?"