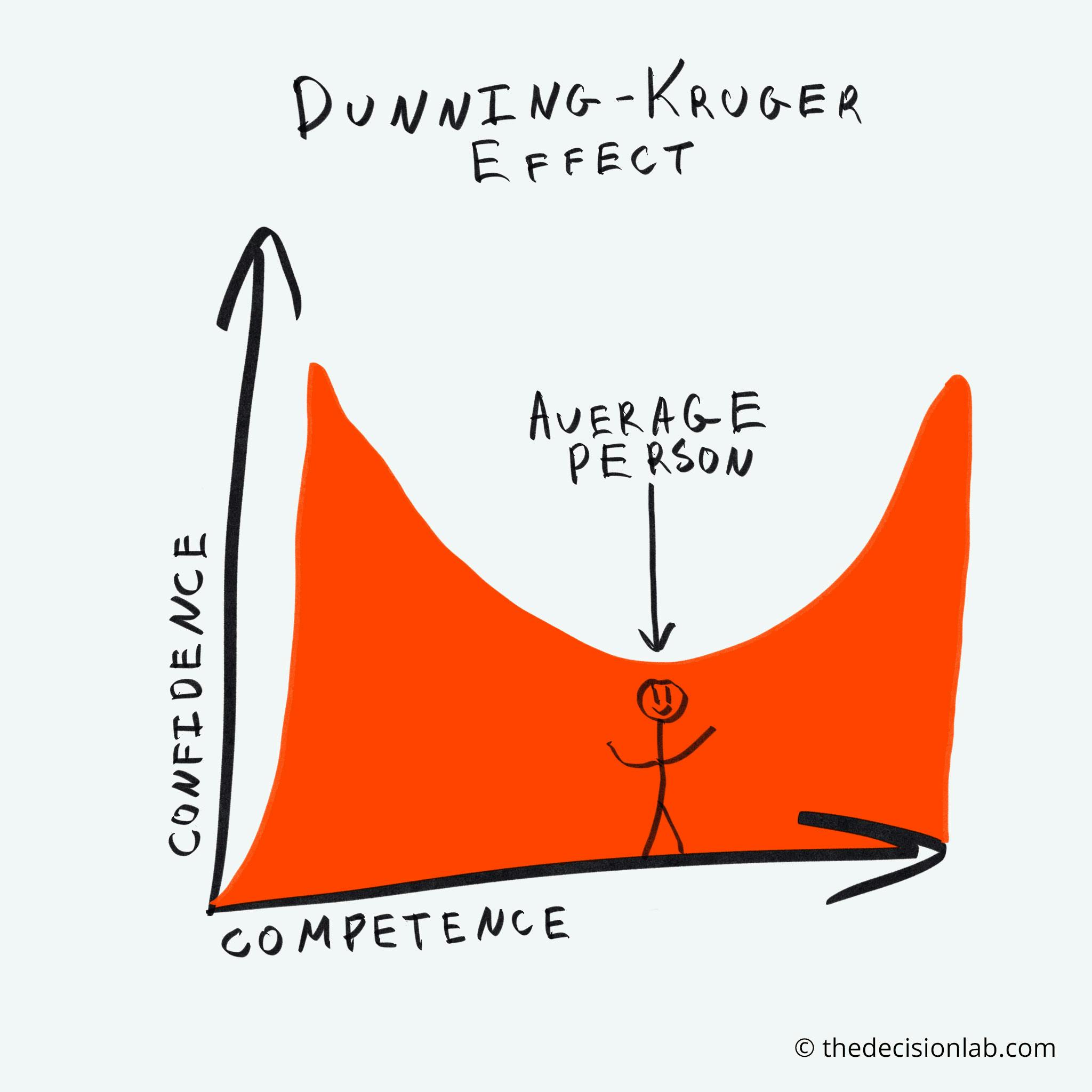

The Dunning-Kruger effect, named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, supposedly highlights a cognitive bias where individuals with limited knowledge or skill in a specific domain tend to overestimate their expertise in that area. This phenomenon arises due to a lack of metacognitive awareness, meaning these individuals are unable to accurately gauge their own competence. Instead, they often harbor an unwarranted confidence in their abilities, leading them to believe they are more proficient than they truly are. Conversely, individuals with genuine expertise may underestimate their competence, assuming that others find tasks as easy as they do, known as the "imposter syndrome."

This feels intuitively true. We all know arrogant fools and wise, modest, uncertain sages. Having a scientific theory/phenomenon as an "explanation" feels validating of the reality of this experience. However, the Dunning-Kruger effect is, ironically, itself an example where a modicum of knowledge in psychology and statistics has fooled many into reading deep meaning into a statistical artifact.

The statistical artifact that underlies the Dunning-Kruger effect can be demonstrated in a thought experiment. It has been demonstrated numerically a number of times, but I think it can be illustrated more simply.

Imagine we have 1,000 robots. We will have them each play two games of chance. We distribute a spinner to each of them. The spinner arcs are divided into a 'correct' and 'wrong' section. The size of the 'correct' arc of each spinner is randomly assigned, to represent a normalized distribution of 'expertise'. This will produce a normal distribution of performance on a test of knowledge. We also hand each robot a die to roll, representing each robot's self-assessment of which performance bin it fell into (rolling a one = 0-16.7%, rolling a six = 83.3-100%).

We then have the robots execute a series of one hundred spins, representing their answers to a test of knowledge. At the end, we have each robot roll a die to represent their self-assessment. Note there is no actual measurement of expertise or metacognition going on with these robots, we are simply generating equivalent statistics to the Dunning-Kruger experiments.

What happens in this experiment is the interaction of the spinner and coin flip distributions creates a skew. No robot can get less than zero or more than 100 "correct" answers. However, those robots at the top or bottom of the performance distribution will appear to under- or over-estimate their performance simply because of the cutoff at 100% and 0%, respectively!

References

An introduction to the Dunning-Kruger effect, a theory-phenomenon that "explains" a lot of things for people:

A takedown of the Dunning-Kruger effect:

A numerical simulation from the above debunker from which our simplified robot thought experiment is derived: